This story originally appeared in The Gulch Magazine Issue 10.

“Look Mr. Whiskers – we found your name again!” We stop to examine another trailside inscription along the sandstone flanking Navajo Mountain.

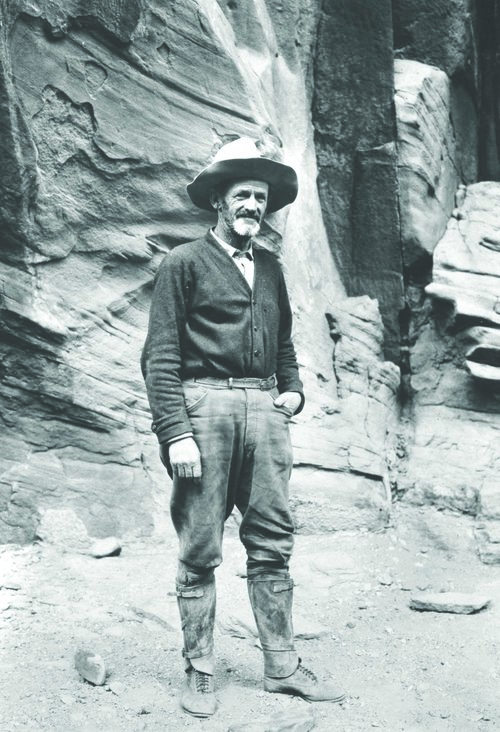

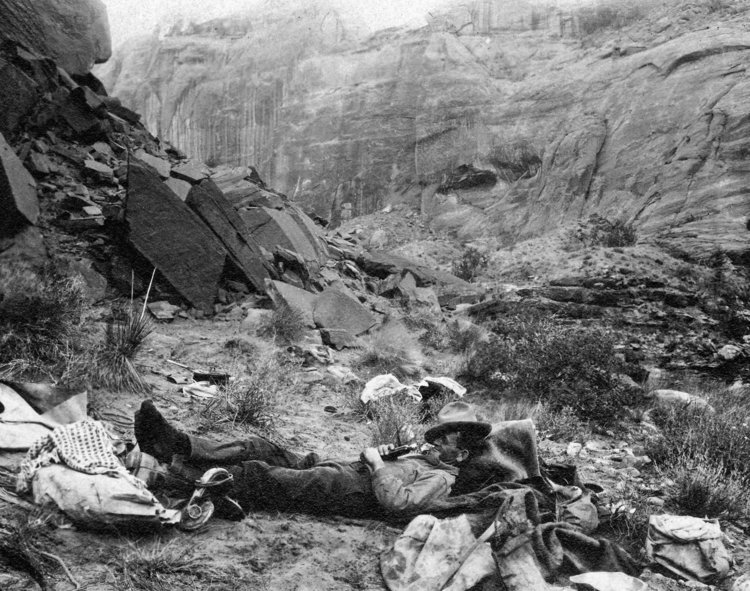

Earlier this spring, my companions Steve and a husky mutt named Phil joined me on a backpacking trip circumnavigating Navajo Mountain. Equipped with a list of historic inscriptions we carefully gazed at canyons walls and boulders in our backcountry game of Where’s Waldo. We focused on inscriptions from the Bernheimer Expeditions, funded by a wealthy New York businessman named Charles Bernheimer who toured the Four Corners region by horseback every summer from 1915-30. We playfully nicknamed each other after the expedition party members: I assumed the role of guide and seasoned desert rat John Wetherill (“Johnny”); and Steve jovially took on the persona of Bernheimer (“Berny”), the self-proclaimed tenderfoot cliff dweller from Manhattan. On an idyllic spring day, with oak buds leafing out before our eyes, we came across a beautiful John Wetherill inscription carved with precise letters on a lavishly varnished sandstone wall deep inside a tributary of Glen Canyon. It was here that we first saw the name CLYDE WHISKERS, faintly scratched in an angular scrawl reminiscent of Ralph Steadman alongside the John Wetherill engraving.

We joked that Phil’s nickname should be Clyde Whiskers so he wouldn’t feel left out from our historical role-playing. Without any clue as to who this person was, we initially perceived it a likely act of vandalism, as is so despondently common across the Southwest. Then we saw Clyde Whiskers carved again on a trailside boulder. And then again on other canyon walls, in a cave and later on boulders farther north. Vandalism tends to be a singular occurrence – two lovers carving their initials in stone or a drunk house-boater memorializing his spring break – but both the frequency and time span of these inscriptions was certainly impressive. Many of the Clyde Whiskers inscriptions were dated within the 50-year cut-off that deems such objects historical versus vandalism. Each time I saw Clyde’s name, or that of a historic explorer, or an ancient handprint, I contemplated what it is about human nature that compels us to leave our names, our handprints, our mark on the world around us?

As we hiked behind Navajo Mountain our curiosity about Clyde rose each time we came across his name. Hauling heavy packs, we’d entertain each other with imaginative tales about “the legend of Clyde Whiskers” as Mr. Whiskers (Phil), whose nickname stuck, trotted with his tail swinging ahead of us along the slick rock domes and narrow canyons. Perhaps Clyde was a sheepherder or a bandit itching for the thrill of leading detectives into the canyon maze; maybe he just wanted to practice his signature. If only the writings on the walls could talk and tell us their stories.

I’ve heard the name Whiskers used in the area only once before – a canyon named Whiskers Draw (formerly First Valley). The only published explanation for the name I’ve found is vague, “First valley had been the site of an incident between a dairy herder named Willard Butt and a Ute Indian named Whiskers. Rancher Butt was alone at his dairy one day when old Whiskers showed up, pulled out a rifle and ordered the farmer to give him dinner. The farmer quickly complied, and to his great relief, Whiskers left pacified. Because of this incident, First Valley is now called Whiskers Draw.” (Blackburn, Fred and Williamson, Ray. Cowboys and Cave Dwellers, 1997. p. 108)

But who was this Whiskers, and was he related to – or even THE – Clyde Whiskers? My imagination often runs wilder than my legs, and these obscure details often lead me to explore new places. So, on a criminally hot afternoon in mid-July, I drive with Phil out to Whiskers Draw, hoping to come across another Clyde Whiskers inscription but certainly not expecting to solve this mystery.

Phil and I walk around the rim of Whisker’s Draw, but his waggly tail and happy panting soon droop along with my own morale. Mid-summer is a brutal time to be out there if you don’t adhere to the well-known desert circadian rhythm: seek shelter and sleep during the day, start making your moves at dusk. Contrary to common sense to avoid the desert in the summer due to scorching temperatures, biting flies and flash floods, it is these times when the desert is its harshest (winter included) that I have had my most profound experiences. We beeline back to the Jeep, down some solar-heated water and leave seeking a place to nap at a higher elevation above Cedar Mesa. Perhaps we will return to Whiskers Draw when the temperatures are cooler tomorrow morning. For the better part of the afternoon, the two of us sleep peacefully in the meadow, and when the temperature finally began to drop, we frolic and run amongst wildflowers and butterflies.

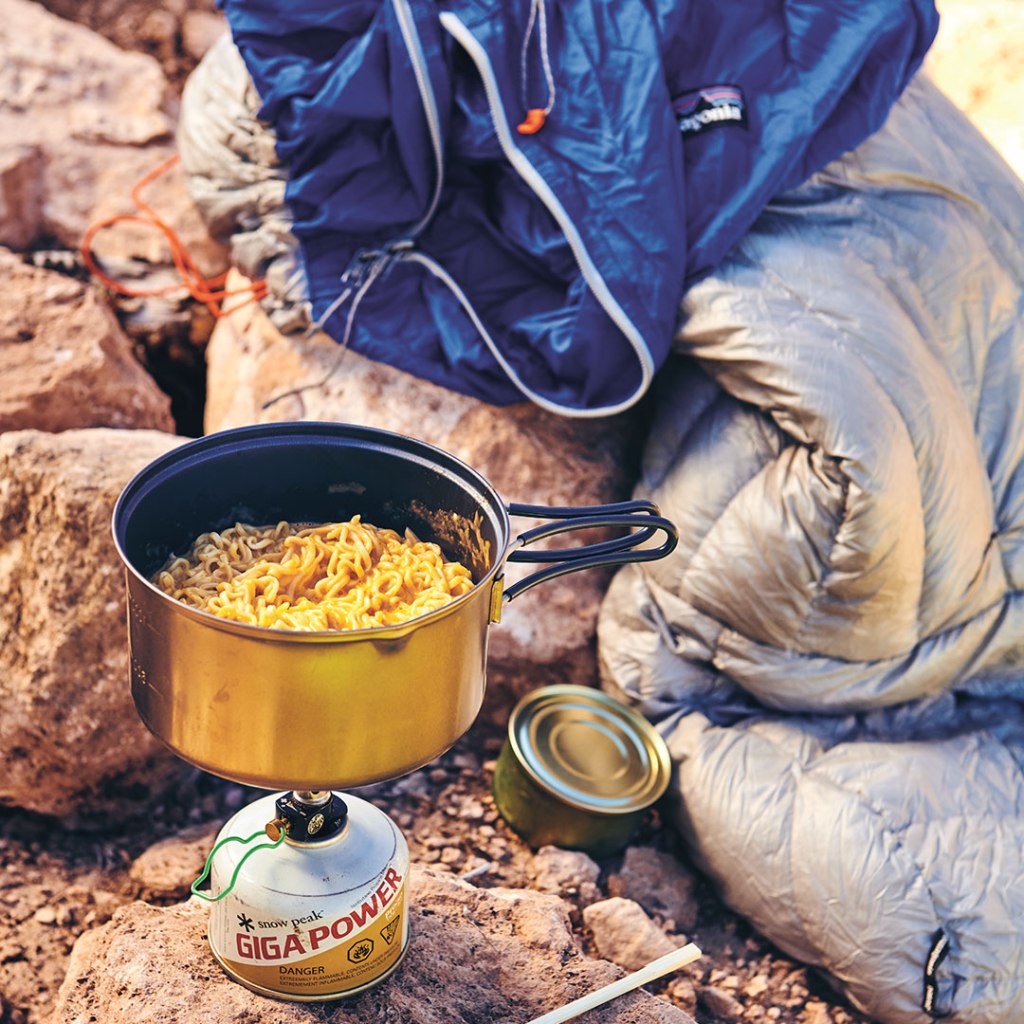

As the sunset behind the shadowed expanse of mesas and mountains, I erect our camp along the ridgeline overlooking the canyon kingdom of Bears Ears and with Navajo Mountain directly before us in the distance. Sitting around a small fire of savory-smelling juniper we wait until the brilliant colors fade before racing to the orange tent to escape the insidious bites of cedar gnats. Blissfully wrapped in each other’s arms, I fall asleep reading a book with my headlamp on. At midnight, I am startled awake. I just dreamt about a man walking around our campsite in the trees with a flashlight. But I noticed there is actually a light moving in the trees. Perhaps nearby campers? My imagination? I want to tell myself that it’s nothing to worry about, that it’s just a bad dream, but what if it’s not?

I gently wake Phil up so I can break down the tent. Fast asleep, he is ambivalent to the situation. He extends his paw out to me, an adorable gesture he makes when he wants to snuggle and hold hands, and I oblige before prodding him to move. When he gets up, the dirt-stained blanket we’ve been sleeping under is covered in dog piss. Yeah, we need to get out of here. Phil wobbles to the Jeep, and I wrongly assume he is just freaked out and tired. He timidly jumps inside and waits while I haphazardly pull apart the tent and stuff it in the back hatch. I get behind the wheel to turn on the ignition and headlights, but it takes me a minute to figure out why I can’t see – then I remember to switch off my headlamp.

Wheels spinning onto the moonlit road, Phil is obviously unwell. He can’t hold his head and body upright or keep his eyes open, and he’s unconsciously drooling and peeing. I drive fearing for his life through the night to get him to a vet and hope he is not as afraid as I am. We stumble into the veterinary office the next morning where, after a series of observations and a panel of blood tests, the vet proclaims her diagnosis, “I think Phil ate some drugs. His symptoms are right in line with eating a psychedelic substance.”

It all seems implausible given that I didn’t have a single mind-altering substance with me, the remote location and the fact that the nearest town to Bears Ears doesn’t even sell alcohol. Then I recall a passage from naturalist Ann Zwinger’s Wind in the Rock, the book I was reading when I fell asleep in the tent. “Datura is one of the main drug plants of the Southwest, it was used ceremonially by the Indians, who made a decoction of the leaves and stems. Generally used to induce visions and for divination, or simply a prehistoric marijuana.” The terminology and accuracy are outdated, but it sparked the realization that datura does grow rampant at our camp, not to mention the plant’s pods (also hallucinogenic) burst open to disperse and spread seeds on the ground. I look down at Phil’s tipsy black and white body and joke, “So Phil Whiskers, why did you eat the datura?” I wonder what sort of incredible visions Phil is having right now:

Phil: I can see things that were hidden before with my eyes closed. Morgan, you missed a bunch of those Clyde Whiskers scratches on the rocks when we were running. I didn’t bark because I was trying to remember where I buried that piece of pizza you gave me. I never chose the drugs; the datura seeds were in the poop I was eating. Do any of us really choose much? I don’t choose to eat the same dog food every day. You always want to go to really hot places – there is no way you are choosing that. And this invisible Clyde Whiskers guy you keep talking about – is he choosing to hike with us every weekend? No way. We should at least find Clyde and invite him to share my hidden pizza. Actually, I forgot to tell you, I think I saw him in the bushes by our camp last night. Mo, are you listening to me? I can’t talk right now, I can only blink. Listen, dammit!

Looking into Phil’s eyes, blinking ever so slowly, it’s as if he’s telling me, let’s find Clyde Whiskers. Or maybe that’s just my sleep-deprived delirium. Jacked up on caffeine and adrenaline, there’s no way I can go back to sleep. Phil, however, sleeps off the drugs for the remainder of the day. Instead, I summon my frenetic energy to send out an email search party for Clyde Whiskers amongst my arsenal of Southwest obscura-obsessed friends. Within an hour, I am on the phone with a man who knew Clyde Whiskers.

“I met him towards the end of his life.” I can hardly believe the conversation as Logan Hebner, an anthropologist from Springdale, Utah, recounts his brief encounters with Clyde. My inquisitiveness skyrockets, but before I can ask another question Logan redirects our conversation, “To understand anything about Clyde Whiskers you need to understand what happened to the San Juan Southern Paiutes.”

The San Juan Southern Paiutes are a semi-nomadic band traditionally based southeast of the San Juan River and extending across the Utah/Arizona border to the land east of the Little Colorado River, in what was formerly known as the Paiute Strip. For a portion of every year, the tribe traveled along a nomadic loop around White Mesa, Douglas Mesa and Allen Canyon – in and surrounding present-day Bears Ears National Monument. The migration around their 9,000 square miles of territory allowed for hunting, foraging, and protection created by the desert landscape.

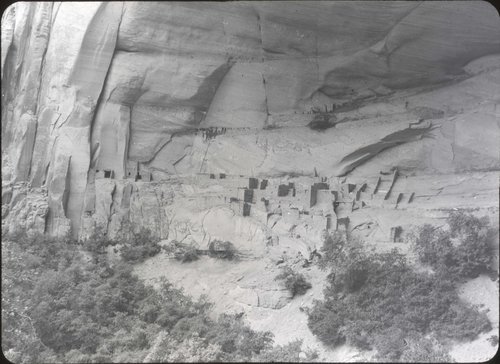

Bernardo de Miera, of the Domínguez-Escalante Expedition, was the first to document the San Juan Paiutes in this area in 1776. This supports their claim to inhabiting these lands before the Diné arrival during Bosque Redondo in 1867 to evade Kit Carson and The Long Walk. (Hebner, Logan. Southern Paiute: A Portrait. 2010. P. 21-22). During the Glen Canyon Salvage Project in 1960, archaeologist Cristy Turner hypothesized, “It is conceivable that the Paiute living on the north side of Navajo Mountain did so along with what we regard as the Anasazi.” (Turner, Cristy. Notes on the Navajo Mountain Paiute Band. 1960)

In 1907, the Paiute Strip was recognized by the U.S. government as an official reservation, but this recognition was temporary. In the 1920s, the U.S. government began prospecting for oil in the region. According to Logan, “Without consulting or informing the San Juan Paiute, Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall vacated their title to the reservation in 1922 and opened their lands for oil drilling. Fall would gain infamy for becoming the first presidential cabinet member to be jailed, convicted of taking bribes from oil companies in exchange for leases on federal lands in the Teapot Dome scandal that embroiled Warren Harding’s presidency.” (Hebner, p. 21). This particular land grab occurred while the San Juan Paiutes were away from their seasonal territory, the government “assuming” that no one inhabited it.

Logan continues, “The oil companies drilled empty holes and left. A young Navajo graduate from the Sherman Institute began petitioning the government to set aside the Paiute Strip lands again, and initial paperwork referring to ‘the Indians who have always lived here’ was gradually replaced with Navajo. There was a series of meetings, from 1930-32, with the Navajo Tribal Council, regional BIA officials and other federal and state bureaucrats – everyone but the San Juan Paiute. In 1933, the vast Paiute Strip officially became a part of the Navajo Reservation.” (Hebner, p. 22) Logan explains, “Most San Juan Paiutes returned home after their migration season with Diné coming to their homes and telling them to leave, that this is no longer their home, and with papers to prove it.”

It’s not a stretch for one to imagine this line from history being repeated contemporarily as federal lands throughout the Colorado Plateau, all once part of indigenous tribal lands, face reduced protections and eased access for extractive industries via illegal interpretations of the Antiquities Act.

In 1954 the U.S. government terminated the San Juan Paiutes as a tribe, not to officially recognize them again until 1989. Today, the San Juan Paiutes still do not have any official reservation lands despite signing a historical treaty with the Navajo Nation in 2000 that would grant 5,400 acres of land to the tribe if honored by the U.S. government. Most live near the Hopi in Willow Springs and Tuba City, or within the Navajo Nation near Navajo Mountain (formerly known as Paiute Mountain, Kaivyaxaru or Ina’íh bi dzil in Paiute).

A former Utah river guide in his own nomadic “living out of a white truck in the desert phase,” Logan spent over 20 years listening to and recording the stories of the San Juan Paiutes, compiling them in Southern Paiute: A Portrait (2010). He donates all of the book’s royalties to the tribe, in a sense paying the elders for their stories. Many (including one 107-year-old woman) recall their days of traditional travel, termination as a tribe, as well as the day they were told to leave their homes. Amongst the stories he recorded, Bessie Owl, Clyde Whisker’s relative, lamented, “It really bothers me sometimes, how we lost this land to the Navajo. This land, it’s not Navajo; it’s Paiute. I don’t consider it as a Navajo reservation. It’s a lease, a lease from the government, that’s how I think of it. I wonder about it, always think about how we would ever get the land back, get a reservation of our own. I was happy when we were recognized as the San Juan Tribe. My husband and I went over to be a part of it. It was a happy moment. But after we got recognized, the Navajo only gave us a little portion of land because they were grazing it.” (Hebner, p. 33)

Many of the Paiutes Logan interviewed did not speak any English, which is how he came to know Clyde Whiskers. Not only did he speak English, he was also one of the few Paiutes with a cell phone, and Logan recalls, “He’d call me late at night about his frustrations about what happened to his band of San Juan Southern Paiutes.” A member of the Tribal Council, Logan recalls that he carried, “a regal embossed calling card proclaiming, ‘Let It Be Known by All That Clyde Whiskers Is A Member of The San Juan Tribal Council.”

“So why do you think Clyde signed his name all over the place?” I ask Logan, and he takes no pause, “I don’t really know, so I’m just making shit up, but perhaps he felt like the Paiute names were being erased from history and erased from the land.” I instantly recall a specific inscription carved on a boulder that I stumbled upon this summer while seeking shade from the hot midday sun. In large bold letters it read: CLYDE WHISKERS SAN JUAN SOUTHERN PAIUTE TRIBE.

Despite the writing on the wall, without an official statement from Clyde Whiskers, these inscriptions remain a mystery, with theories from a couple of white people and a dog on drugs walking around in the desert using their imaginations. In following my curiosity about Clyde Whiskers, I reached a point where I had to suspend my own ideas, ask questions, wait patiently and listen to stories left out of the history books. My enigmatic fantasy and quixotic quest to find Clyde Whiskers led me to unexpected truths.

A few days later after the drug incident, I drive six hours to the Utah State Historical Society in Salt Lake City, housed in the former Rio Grande Depot train station built in 1897. Today it is a museum and archive of Utah government and historical documents, including the one and only file created for Clyde Whiskers. Inside, I spend 45 minutes explaining to the bookkeeper that her computer catalogue is wrong, there is a file for “Clyde Whiskers” stored here. She rallies one of her colleagues, and after another lengthy round of digging, they roll up a massive cart piled with boxes and wish me good luck. I have 15 minutes until the building closes. I race the clock navigating the files with tunnel vision, confident in my eyes – if I can find “Clyde Whiskers” faintly carved into obscure sandstone walls, I can pick out his name written on a manila file. When my fingers graze across the file, my heart leaps in the same way that etchings on a sandstone wall make the world around me stop. And then I remember the clock and run to the scanner – I’ll copy the documents now and sift through them later.

Afterward, I sit down with a cold beer to examine my photo copies. Within the files, there is a list created by historian Jim Knipmeyer documenting Clyde Whisker’s inscriptions with the details, dates and locations spanning 49 years – truly a lifetime amongst these canyons. I read it and vividly recall the Clyde Whiskers inscriptions I’ve encountered.

In May, Steve and I spotted a large cave in the distance. We decided to check it out, which required crossing in and out of a few shallow canyons as storm clouds drew nearer. When we arrived at the base of the alcove, a series of moki steps carved into the sandstone led up to the entrance. Steve led the climb and nimbly gained the ledge with his camera in hand, “Come on up Johnny!” As I gripped the shallow hand and toe trail, a gust of wind whipped my hair into my eyes, I shook my head to move the hair from my vision, taking in a most spectacular view of Navajo Mountain in the process. Once in the cave, I immediately spotted Clyde W drawn in charcoal on the dusty pink wall. The spot also contained an old fire pit, and I imagined this being one of Clyde’s secret camp spots. I wondered how many other obscure places Clyde wrote his name in over the years that were yet to be encountered.

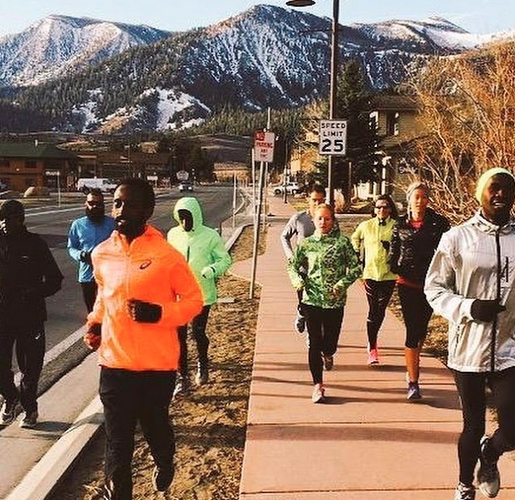

The next day, on an 18-mile run along the Rainbow Trail, Clyde’s name frequently jumped out at me as if to say “Hi” as I swiftly moved up and over the bald rock domes of sandstone. The minute details even more striking amidst competing views of the greater Grand Staircase and Glen Canyon drainages. Often his name accompanied others that I now recognize as Paiute, like Joseph Lehi, bold drawings of horses and portraits of Paiute men. Despite keeping an honest pace over the hilly terrain, I seemed to be setting a personal record for seeing rock art, as I took note of far more inscriptions than when I walked this same route much slower. I reminded myself to email my friend David Roberts about this later, as we have a playful ongoing debate about the best pace for spotting rock art. While David thinks it’s bullshit that I see more rock art when I’m running than walking, I credit the heightened awareness and tunnel vision that comes with the runner’s high for this enhancement.

Ironically, David also planted a seed of inquisition when I read a story he wrote (fittingly) about Mystery Canyon in his book In Search of the Old Ones, “I was beguiled by a defiant 1986 inscription I found along the Rainbow Bridge Trail: CLYDE WHISKERS PAIUTE INDIAN.” (p. 200) When I asked David if he knew anything about Clyde Whiskers, he confirmed that he was a San Juan Paiute and potentially that he was a relative of Paiute leader Angel Whiskers, perhaps linking him to an AW inscription that David found in Mystery Canyon. Here running on the Rainbow Trail, these Clyde Whiskers inscriptions motivate me to run just a little farther, over one more hill and around another bend in the canyon where, perhaps, I’ll find one more clue.

The San Juan Paiute’s presence is marked along the route to Rainbow Bridge and around Navajo (Paiute) Mountain. In 1909, Professor Bryon Cummings, W.B. Douglass and John Wetherill enlisted San Juan Paiute guides Nasja Begay and Jim Mike to help them become the first non-natives to document visiting Rainbow Bridge. The San Juan Paiutes successfully led the party to the stone rainbow, followed by a friendly controversy over which white guy spotted the bridge first. Today, Nasja Canyon is named in honor of Begay in addition to plaques honoring him and Jim Mike placed at Rainbow Bridge. Despite that recognition, homages to the San Juan Paiutes are few here, unless you factor in Clyde Whiskers and the accompanying San Juan Paiute names and artwork.

As I wander around the desert, Clyde Whiskers’ name continues to pop up. My heightened curiosity bordering on madness, I scan the walls where Clyde Whiskers, like the Cheshire Cat, continues to elude me. Despite the seeming impossibility of ever knowing who Clyde Whiskers was, let alone meeting him, stopping now feels like giving up before pushing a slot canyon to its end. And yet, I contemplate whether I already know too much. It’s these types of mysteries that are at the core of what I love about the Colorado Plateau, the kind of place where you can explore forever without encountering all of its secrets or unearthing its hidden stories. Like the elusive landscape, we may never understand the petroglyphs, why people leave their names on walls, what type of drugs my dog took, the namesake of an obscure canyon or whether the man in the forest was a dream or reality.

For the sake of complete reporting and investigation, I forge on and dig up a contact phone number for the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribal Council. I want to talk to a member of the tribe who knew Clyde, perhaps a link to one more detail, a link to understanding why this man felt so compelled to leave his mark across the desert. I dial and an operator picks up.

“Hi, my name is Morgan Sjogren, and I am working on a story about one of the former members of your tribal council. I’m wondering if you can help me locate any records or connect me with anyone who possibly knew him.” I am relieved that my unusual inquiry comes out intelligibly.

“Hmmm, well, that’s not really my job. Who are you looking for? Maybe I can help you.” The San Juan Paiutes are a small tribe, this shot in the dark could be as good as any.

“Clyde Whiskers.”

The woman immediately snickers, “Oh Clyde. Yeah, he’s still around.”

“Wait, like you mean he’s still alive?” She confirms, and I thank her profusely. Imagine her confusion in hearing my excitement that some guy she sees around town all the time is alive.

I put down my phone and grab my running shoes. It’s time to head back out into the desert to try to find Clyde. Perhaps he is lurking in an alcove waiting to find me. Back in my Jeep on the highway across the Rez, the warm air whips my hair into my face, as I take in views of my favorite landscape features – Comb Ridge, Bears Ears, Monument Valley, Agathla. On a whim, I stop in Tuba City, pull out my notepad and scribble a message and my phone number and leave it with the woman I called earlier. I am hopeful that an old-fashioned note will travel faster than a text message out here where cell service rarely exists. I reassure myself that now I have done everything I possibly can to track down Clyde, that I can in good conscious move on from this mystery.

Less than an hour later, with the Painted Desert in my rear view, my phone rings. I answer without looking at the number, “Hello Morgan? THIS IS CLYDE WHISKERS.” Is this a dream? I immediately pull over – when the canyons call, you listen. His voice is strong and clear, and he is eager to talk to me. We agree to meet at McDonald’s the following weekend. I enter Clyde Whiskers into my phone contacts and hope that this isn’t another dead end. But it can’t be – Clyde Whiskers found me! Clyde proceeds to call me every single day and then hourly on Saturday, to confirm that I am actually still meeting him. The check-ins feel familiar, like seeing his name pop up on my long hikes and runs. I assure Clyde I would not miss this meeting for anything.

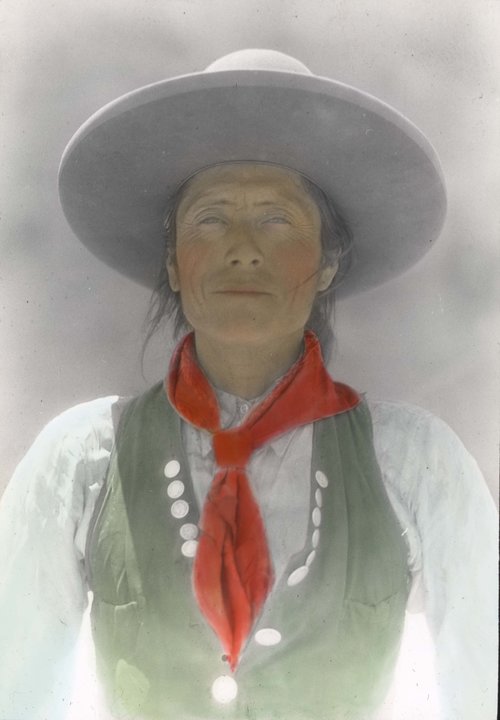

On a hot Saturday afternoon, I walk into McDonald’s but don’t see any men over 16 years old. I call Clyde again and walk back out the front door where a short stout man with white hair and whiskers answers his phone, “Hello Morgan!” He looks up at me with a big grin as I say, “Hi Clyde!” into my phone. We both laugh as we hang up our phones. I am in complete awe – in some ways this man has joined me on more recent adventures in the desert than anyone else. We both are reserved with our conversation and decide to head across the street to the Hogan Restaurant where we can sit down for a proper meal and talk.

Once we are at the table, Clyde is direct, “So how did you find me?” I explain the long saga, including nicknaming a dog after him, to which he intermittently interrupts, “Yeah, I been everywhere.” He immediately shares a flurry of places where he signed his name, including some spots high off the ground during his brief stint at rock climbing, “But it was too dangerous, you know.” Despite having a head full of questions, I am simply interested in getting to know Clyde, the once-elusive canyon scribe, and receiving the stories he is willing to share with me. His explanation for his inscriptions at first seemed simplistic, “It’s what I did. I wrote my name everywhere.” But in between bites of his Salisbury steak, the layers leak out. “Yeah, my uncle Angel Whiskers taught me to write my name, you know.” Later in his life, on a Grand Canyon river trip with other San Juan Southern Paiutes, Clyde first learned about the modern consequences of carving your name on public lands and has since acted accordingly, “We don’t do that anymore. It’s what we used to do, not anymore.”

His stories about his name inscriptions blend into what happened to the San Juan Southern Paiutes and specifically, “The Navajo keep erasing our names out there. Navajo Mountain used to be Paiute Mountain, you know.” He talks about his parents losing their land to the Navajo, reminisces about his youth grazing sheep on the flanks of Navajo Mountain and recalls the horror when he first saw the waters of Lake Powell flooding the surrounding tributaries of his home near Glen Canyon. Amidst these attempts of newcomers to rename and reshape the land that the San Juan Southern Paiutes called home, Clyde wrote his name. Eventually Clyde took to more formal writing, spending 10 years helping compile the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribal Constitution. While he is no longer a member of the Tribal Council, he remains engaged with tribal politics and is eager for the day when the San Juan Paiutes have tribal land of their own again.

“They don’t put Paiutes in books like they do Navajo, you know.” Clyde reaches into a plastic sack he carried along and pulls out some papers. “One time there were other guys out at Paiute Mountain writing stories too. They wrote about us. I never met them even though I was out there. Maybe you know them?” He hands the paper across the table and my heart leaps–it’s a photocopy of David Robert’s Mystery Canyon story from In Search of the Old Ones. “Clyde, I know David!” He puts down his fork and smiles, “Then you can tell him AW is my Uncle, Angel Whiskers.” One of the final conundrums of Mystery Canyon resolved by the mystery man himself.

I reach into my belongings with an offering of my own, “Clyde, they didn’t leave the Paiutes out of this book.” It’s Logan’s book about Southern Paiutes. I open the pages to show Clyde where members of his tribe also mention him in their stories. “Yeah, I knew her, Bessie. And that’s Jack, and Mary Ann. And I remember Logan, too.”

His pride for his heritage is unflagging, and at one point he pulls out his wallet to show me his official San Juan Southern Paiute Tribal Card, which he only recently received despite the tribe’s official recognition in 1989. As he thumbs through his wallet, his driver’s license catches my eye: Clyde Kluckhohn Whiskers. It’s a fantastic detail as Clyde Kluckhohn was a young adventurer who explored the Southwest by horseback on a dirtbag budget in the ’20s and ’30s. He went on to write two books about his explorations, (To the Foot of the Rainbow and Beyond the Rainbow). Additionally, his encounters with tribes along the route, including Paiutes in Navajo Mountain, inspired him to pursue a career in Southwestern anthropology. “Clyde, you were named after Clyde Kluckhohn the adventurer?” With his trademark pride, he confirms although he doesn’t know if his parents ever met the other Clyde. “He was famous, you know. In books.” I look into Clyde’s kind eyes, “You are, too, Clyde, you’re in a lot of stories now.” For a surreal moment, I feel the adventurous spirits of Clyde Kluckhohn and David Roberts joining me and Clyde Whiskers in Tuba City, eager to trade stories and tease one another with hints of new mystery spots.

“This is like a dream. The dream is right here.” Clyde looks at me and I feel exactly the same way. He clutches the Southern Paiute book with his right arm, where “Clyde” is tattooed in script letters across it.

What an indelible impression that this man’s name has left on me, and on this Earth. History is a mélange of the incomprehensible and questionable – impossibly layered by time like the geographical forces that shape the canyons and mountains; here the truth is always embedded, but often difficult to find. And perhaps this is why it is so human to etch our names, our handprints, our history with sharpened point or ink, on stone and skin. Like Clyde Whiskers and the San Juan Paiutes, we don’t necessarily need all the answers, we need to exist.

Morgan considers the Colorado Plateau territory her home, where she runs wild chasing stories and adventure. Her Four Corners-inspired writing is focused on public lands, human-powered adventure and exploration. She is the author of three books: The Best Bears Ears National Monument Hikes, Outlandish: Fuel Your Epic and The Best Grand Staircase National Monument Hikes (available in October).

What her story—set in the American Southwest—reveals about the future of our public lands

What her story—set in the American Southwest—reveals about the future of our public lands